|

Eager Space | Videos by Alpha | Videos by Date | All Video Text | Support | Community | About |

|---|

Dongfang hour

https://dongfanghour.com/

Andrew Jones

https://spacenews.com/author/andrew/

China-In-Space

https://china-in-space.com

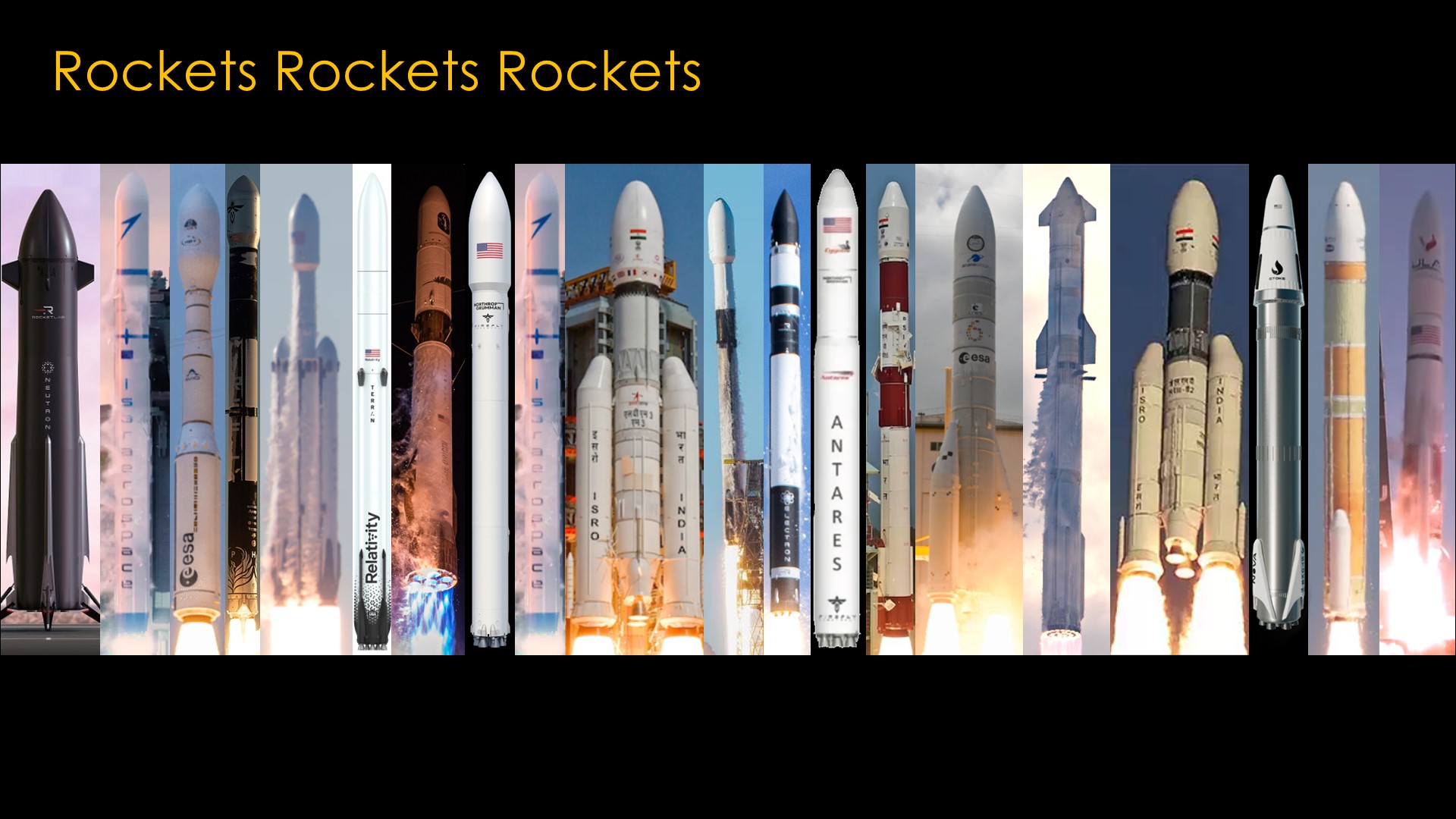

I talked about launch markets in part 1, and now it's time to talk about rockets. There are a lot of rockets to talk about...

It's not enough for a rocket to be technically good, it has to be competitively priced and have enough capacity for customers to buy launches on it, and that means the success of the rocket is directly tied to the organization that is building it.

We'll start with small rockets

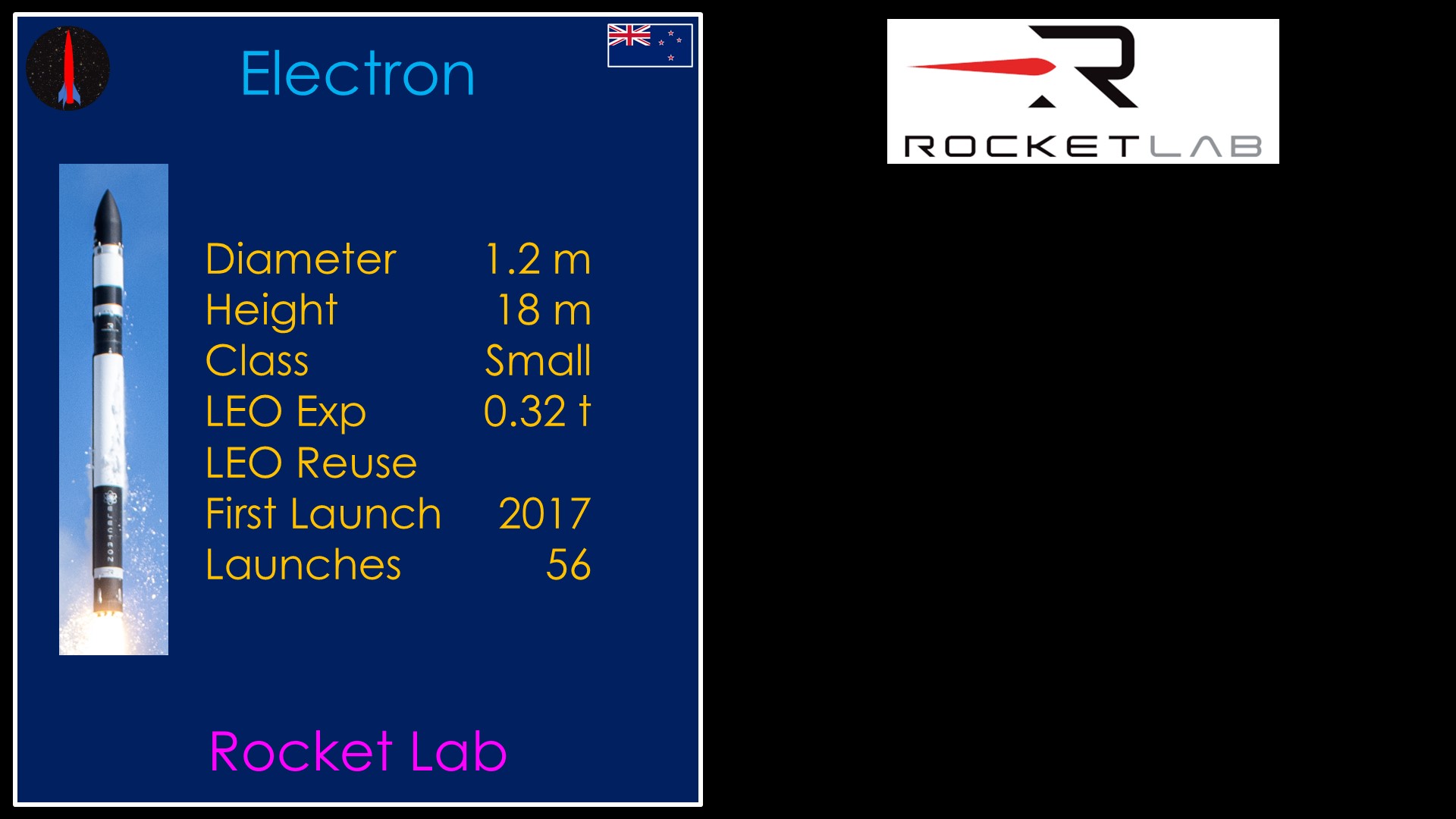

At 56 successful launches, Electron from Rocket Lab is third place in number of launches of the rockets that we are going to look at today.

Electron dominates the "small payload where I need to control the exact orbit and launch schedule" market. It's not a big market - at 15 launches per year at around $7.5 million a launch, it's a little over $100 million per year.

Electron also launches hypersonic test vehicles for the US government as part of Rocket Lab's HASTE program.

Rocket Lab is hoping to launch more than 20 Electrons in 2025.

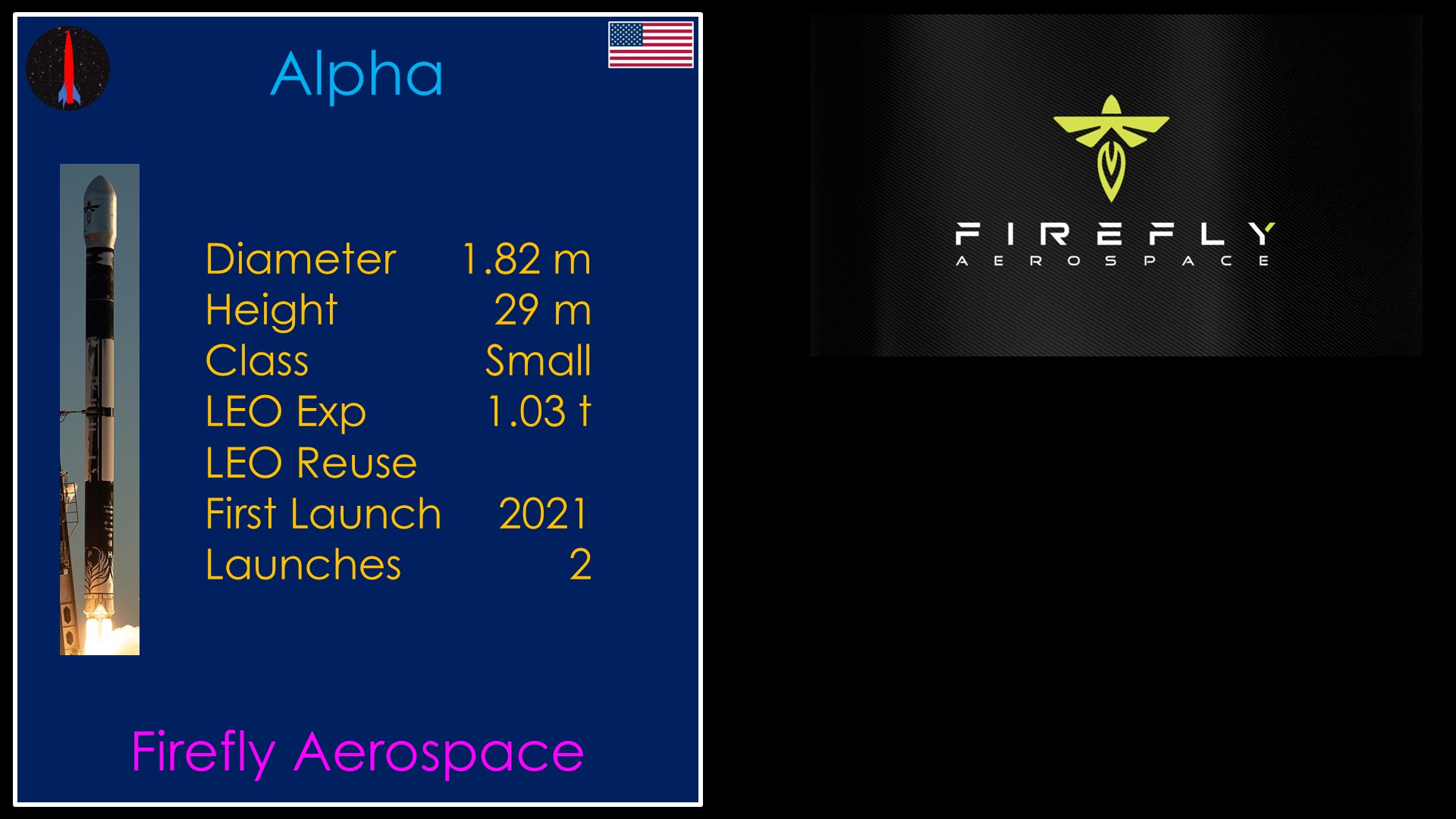

Firefly Alpha has flown successfully two times, once in 2023, once in 2024.

It does have some launch contracts - Lockheed Martin committed to 15 launches with options for a future 10 launches. L3Harris has also signed a multi-launch agreement to fly on Alpha. That is a good backlog for a small rocket, but - like Electron - there's not a ton of money overall.

Both Rocket Lab and Firefly have bigger rockets under development.

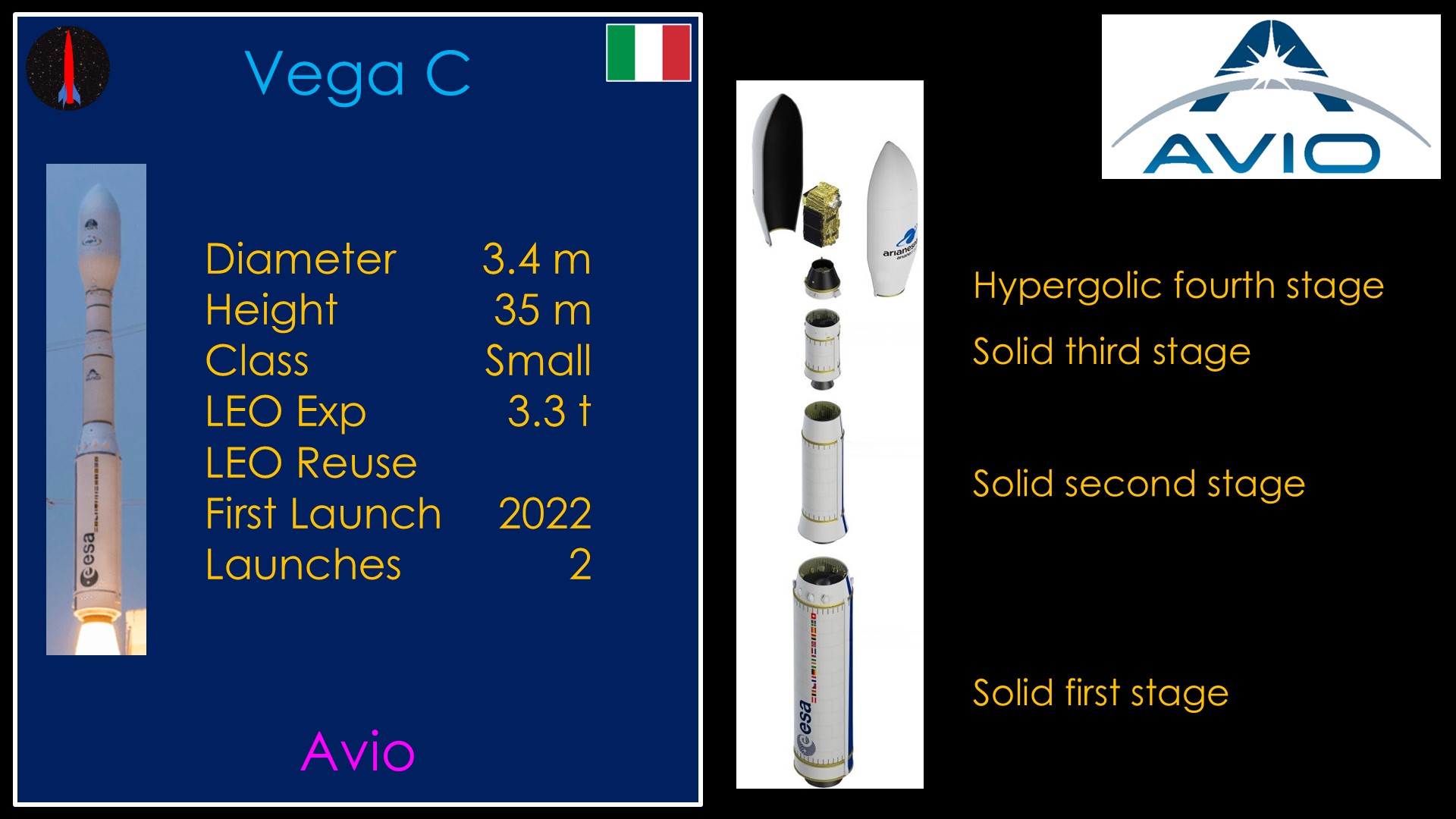

Next up is Vega C, the newest version of the European vega rocket, which has done about 20 launches. It's a weird rocket, with a solid first stage, solid second stage, and solid third stage, topped by a tiny hypergolic fourth stage. It was originally operated by Arianespace but is in a transition to where Avio will launch Vega C commercially.

As Europe's only small launch vehicle, it has a backlog of 18 flights for 2025 and another 8 flights in 2026. That is a decent but not huge market.

It launches from Arianespace's launch site in French Guiana.

Vega is a costly rocket, with launches costing $35-$40 million.

There are a few upstarts that might take a bit of Vega's business or pull some new business.

Spectrum from ISAR (E sair) aerospace in Germany is one. At 1 ton of cargo, it's about a third of the size of Vega.

They have two planned launch sites. Northern Norway for polar launches, and French Guyana for normal LEO launches.

The second is RFA One from rocket factor Augsburg. It's a little bigger than Spectrum.

They plan on launching from Saxavord space port at the northernmost part of Shetland Island in the United Kingdom. It has easy access to launch into polar orbits but launches to the east are probably not possible as they would overfly Norway and Sweden.

Both Spectrum and RFA One are scheduled to launch in 2025.

We now move onto expendable medium class rockets, and we'll start with three rockets from the Indian launch organization, ISRO. They win the award for the least creative rocket names.

The polar satellite launch vehicle which has been flying since 1993.

Next up is the Geosynchronous satellite launch vehicle.

And we end with the launch vehicle mark 3, a derivative of the GSLV

India is very serious about their space program and will likely become the 4th country to launch humans into space in the next few years.

I expect to see a lot more activity from ISRO in the future.

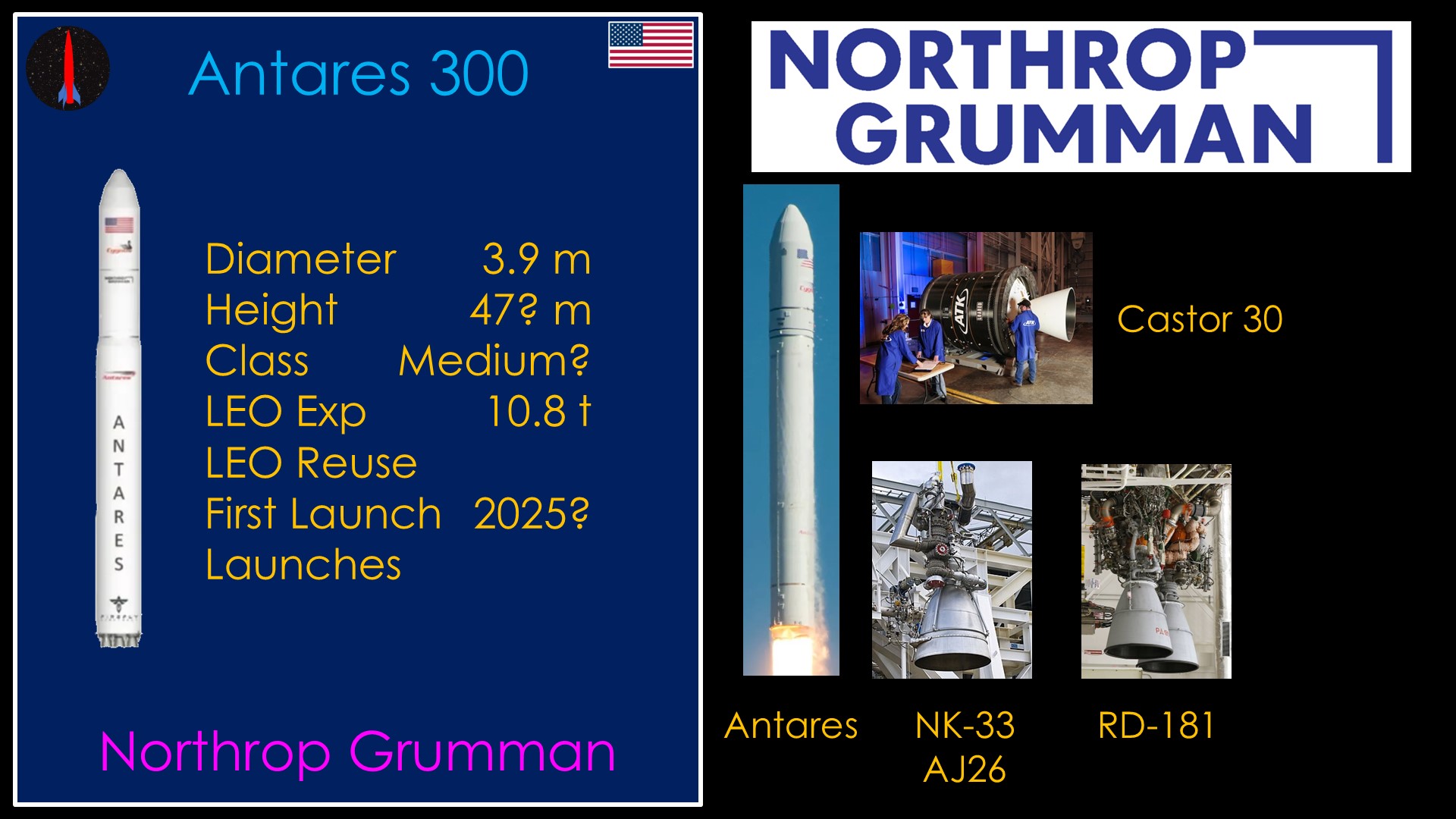

Next up is the Antares 300 from Northup Grumman.

The Antares came out of the same COTS program that gave us Falcon 9. It's another weird rocket.

The first version of Antares used two NK-33 Russian engines, the same engines that were used on the Soviet N1 moon rocket in the 1960s. Not the same design, actual engines that were built in the 1960s and then remanufactured by Aerojet and renamed the AJ26. After a failure of a turbopump in testing, the Antares 100 series was retired.

For the Antares 200, the more powerful Russian RD-181 engine was chosen.

The second stage is a solid rocket motor, one of the variants of the Castor 30.

In addition to launches of the Cygnus resupply capsule, Antares has launched commercial payloads, fulfilling NASA's goals for the COTS program.

Just kidding. Antares is a one trick pony, it has 17 successful launches and every single one of them has been a launch of the Cygnus resupply module to the ISS.

Like ULA's decision to use the RD-180 in Atlas V, the decision to use Russian engines would turn out to be a poor choice in the long run, and that meant a new first stage was required. It takes time to develop a new rocket, so Cygnus is currently launching on Falcon 9.

The Antares 300 uses the stage 1 of the medium launch vehicle from firefly aerospace that we will talk about later, married with the same second stage. It will push the payload up quite a bit.

The Antares 300 confuses me. If the first stage works as planned and is on time, they can at best get 9 resupply missions out of it. That's not a lot of flights to make back the development expenses, but maybe in combination with the medium launch vehicle it makes sense. But it would be a whole lot simpler and less risky to just fly on Falcon 9.

I expect the Antares 300 will have the same level of commercial success as the previous versions.

The Japanese H-3 has now had 4 successful launches. No LEO payload given but 5800 kg to GTO and I estimate about 14 tons to LEO.

It's primarily a home market rocket and will launch Japanese government payloads, along with a couple of comsats.

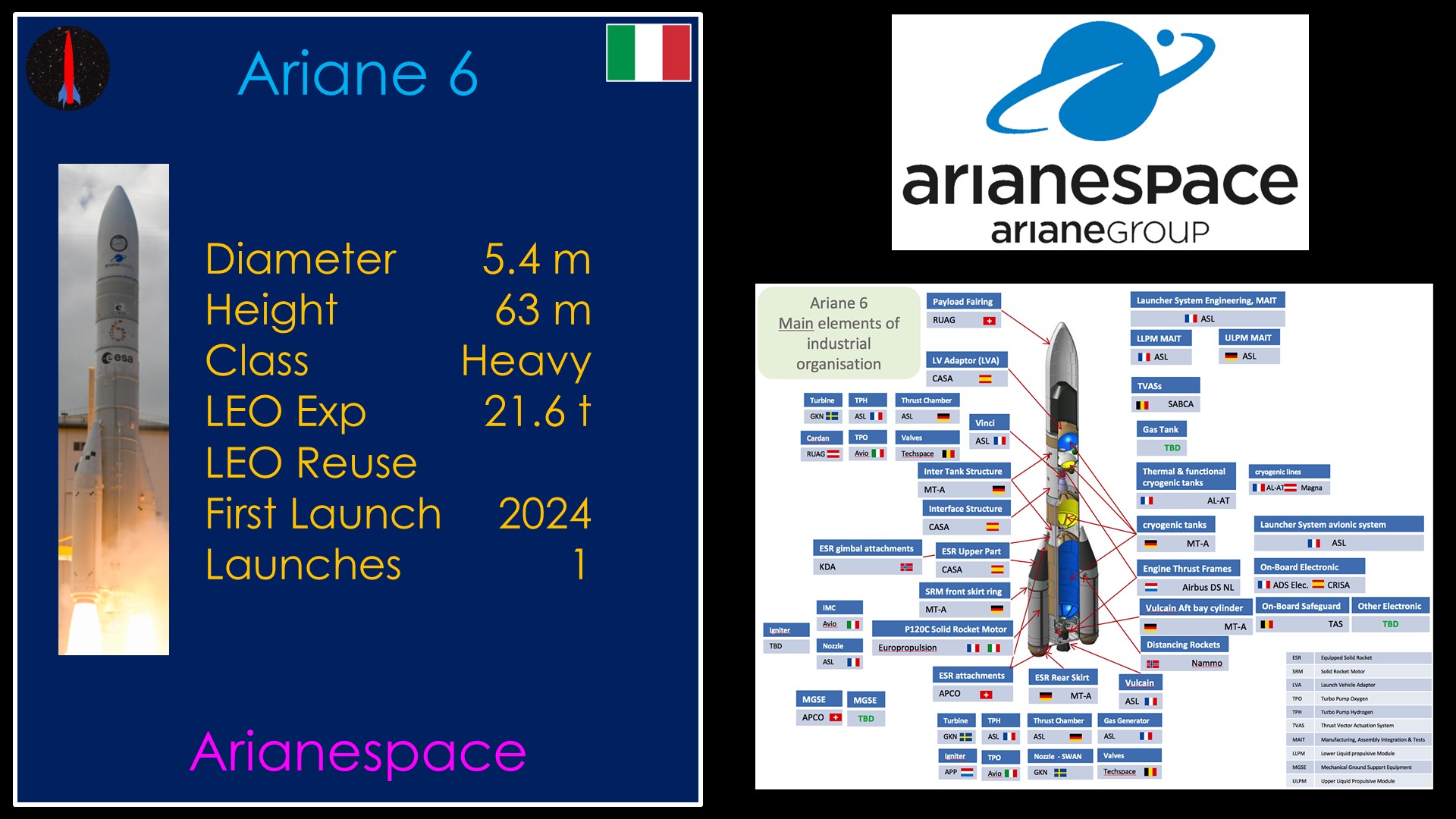

Ariane 6 is the successor to the hugely successful Ariane 5 launch vehicle from Arianespace.

Because it is a few years late it has a pretty good launch backlog, include contracts to launch Kuiper satellites for Amazon. The geosynchronous satellite launch market has shrunk a lot and the delay of Ariane 6 pushed the majority of contracts to Falcon 9 or Falcon Heavy and it's not clear what will happen in the future.

Arianespace is a bit like NASA in that they buy different parts of their rocket from different suppliers, but it's more complicated because a single component like the Vulcain main engine has parts from 4 companies across 7 countries. That makes it very hard for them to be agile.

It will continue to fly as the European heavy lift rocket, but I do not expect that it will have the commercial success that Ariane 5 had.

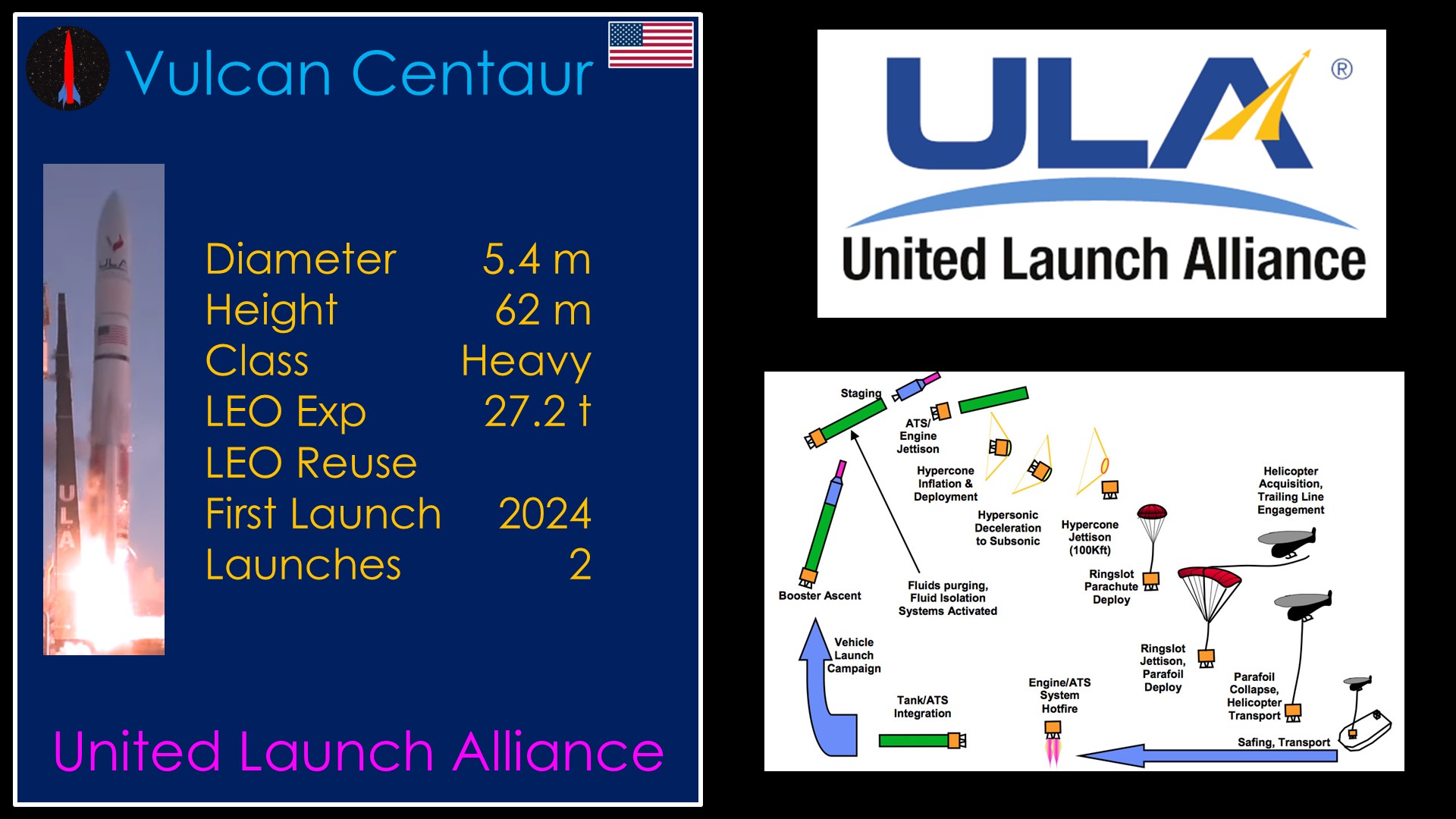

Vulcan is ULA's replacement for their Atlas V and Delta IV Heavy rockets, and has flown twice.

It has a large backlog of space force payloads to launch - large because it is at least 2 years late - and that backlog will take some time. It also has contracts for quite a few Amazon Kuiper launches.

ULA stands to do pretty well with Vulcan if they are able to achieve a decent launch rate of at least once a month and if the Kuiper and future space force launches come their way, but as the space force market becomes more competitive and new options such as rocket lab's Neutron and perhaps Blue Origin's New Glenn show up, they are going to come under increasing competitive pressure.

Vulcan Centaur stages very late and that makes propulsive landing of the first stage impractical; they may deploy their much discussed "SMART" reuse architecture if their flight rate gets high enough, but I don't think that will save them enough money to be competitive in the long term.

We now move to reusable launch vehicles.

Next up is MLV, a medium class launcher from Firefly aerospace, though from what I can tell we should probably call this a collaboration between Firefly and Northrop Grumman since they are both claiming the rocket.

It's an expendable rocket with reusable aspirations.

As an expendable rocket it will need to fight for market share with the partially reusable rockets and that probably won't end well. As a reusable rocket it might work better but getting enough contracts for a high enough flight rate to compete may prove to be problematic.

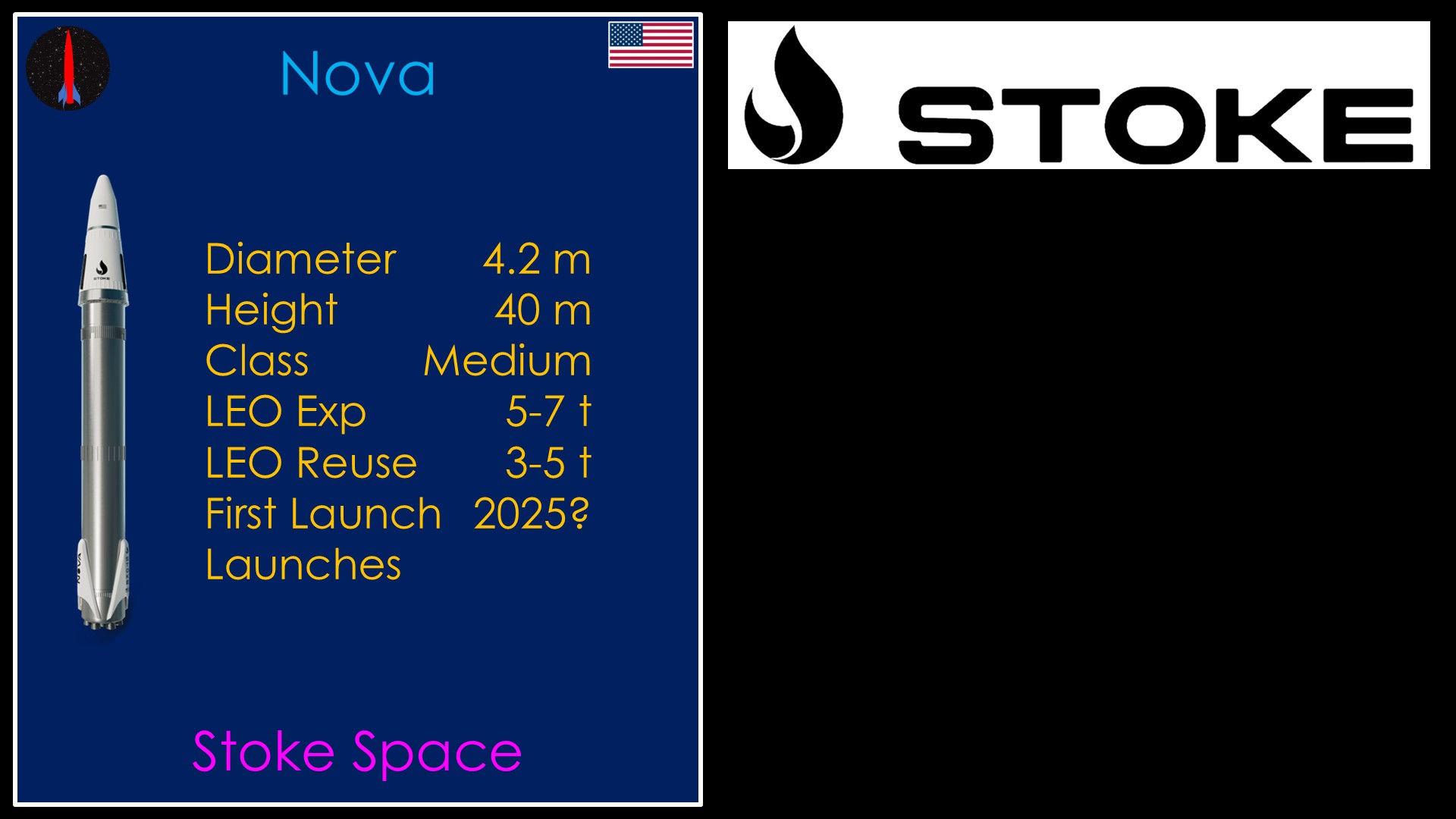

Up next is Stoke Space's Nova, and it's great to see more details come from the company.

Their current targets are 3-5 tons into low earth orbit fully reusable and 5-7 tons with one of the stages expended. That is considerably lower than many of the other medium launch partially reusable rockets, but it's a good place for them to start and keep their vehicle a reasonable size, and with new technology a smaller vehicle is generally better because it is cheaper to develop.

I'm still withholding judgement on the effectiveness of their second stage reentry system, but they are making the right moves as a company. In January they raised $260 million in a Series C funding round, which should be enough for them to get through at least their first test flight and prove their concept.

New concepts are inherently risky but they are also the ones with high reward.

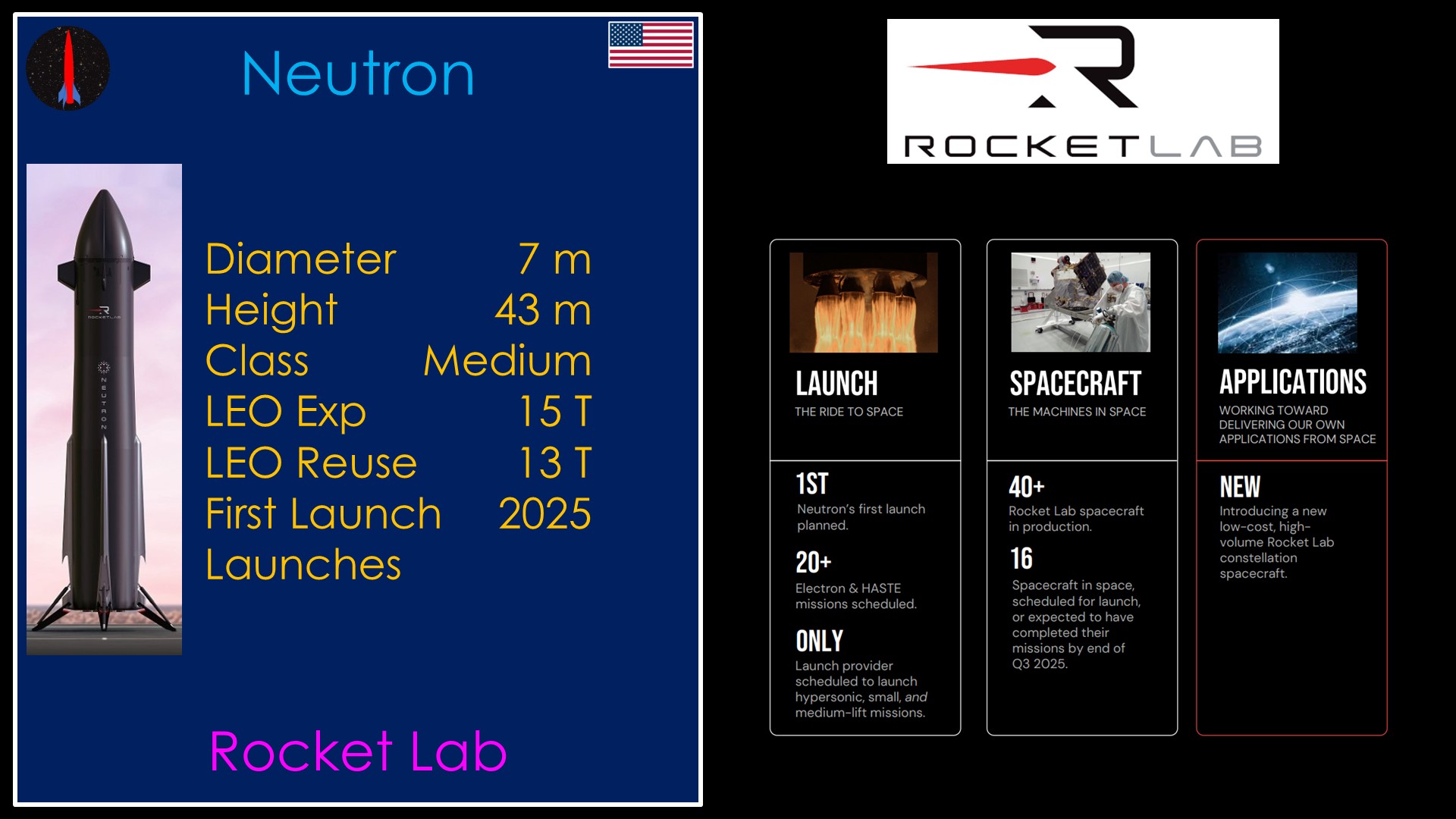

Neutron is the first partially reusable rocket built from first principles, and I think that gives them a decent chance to be cheap enough to find a good market. Neutron will probably fly sometime in 2025 or, if not, early in 2026.

Many people miss that Rocket Lab is not a launch company, they are an end-to-end space company who already makes more money from their space systems division than from their launch division.

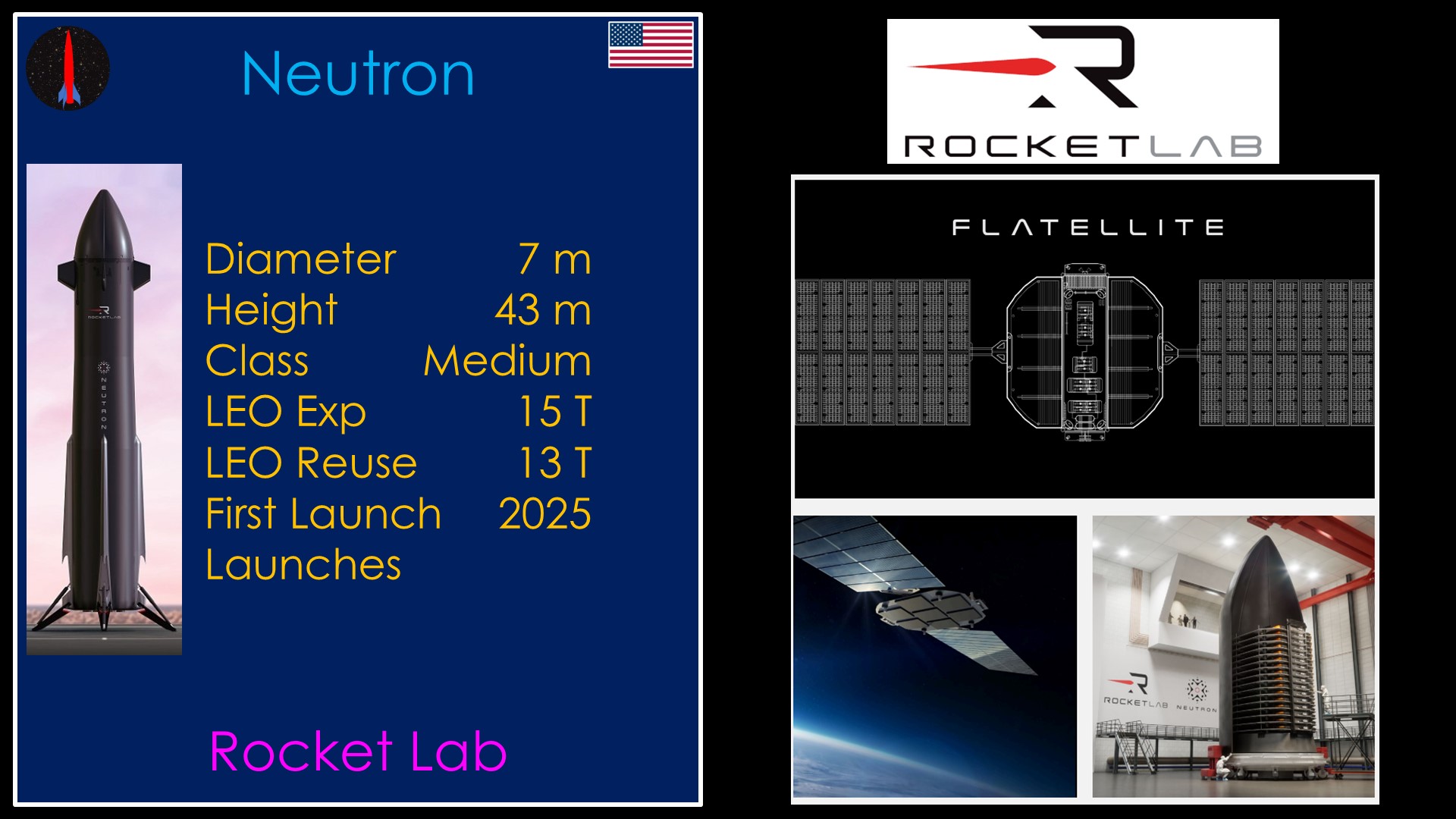

They are planning to push farther into that world with their recently announced low-cost flatellite satellite. Like Starlink, it is a satellite design intended to maximize the number of satellites that can be fit into a specific rocket fairing. There's no news on whether they are planning their own constellation or are selling the design to others, but to be able to buy a set of satellites off the shelf could be a significantly cheaper option for many customers.

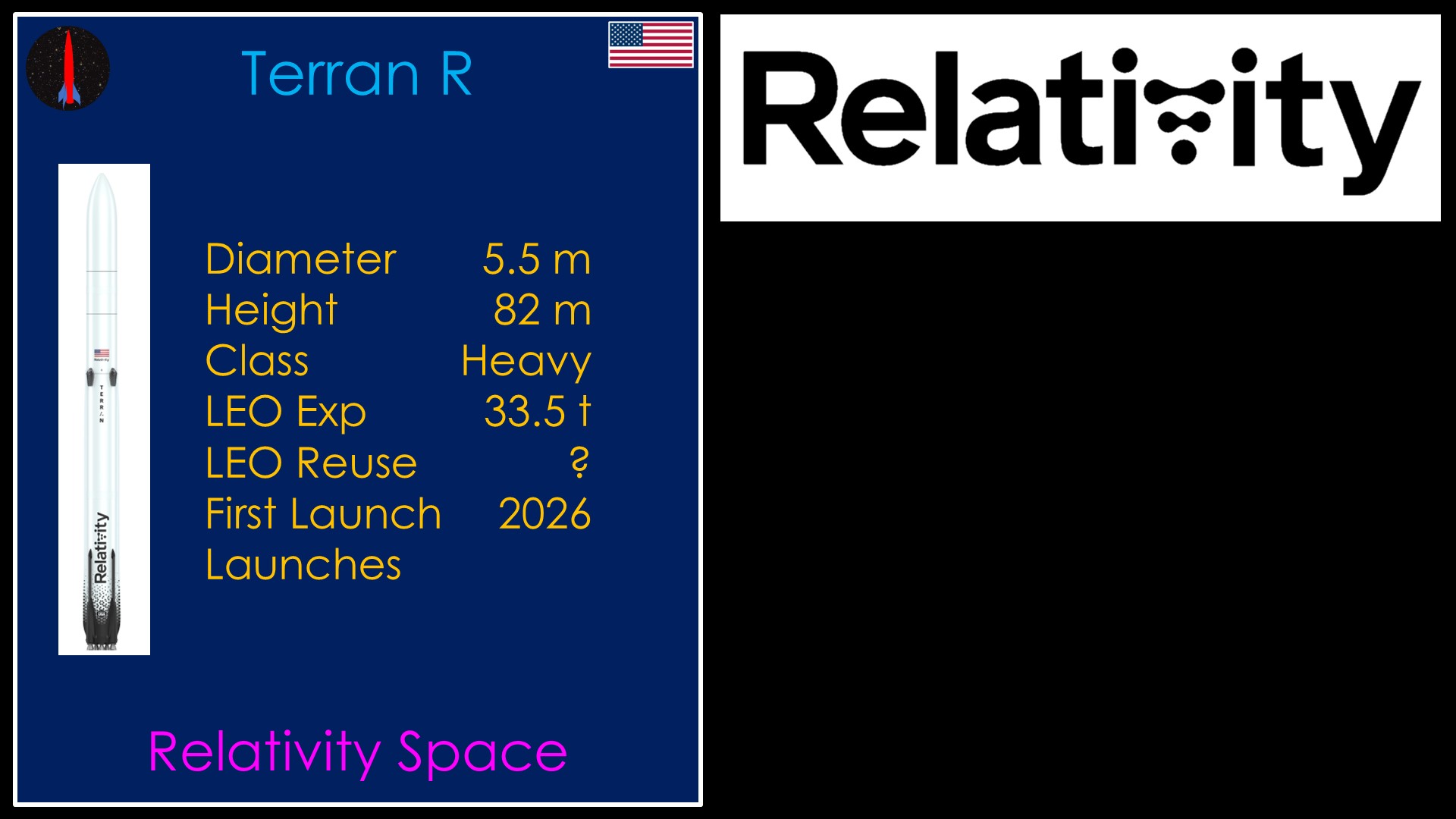

It's hard to find much information on Terran R or relativity space. Relativity launched their much smaller Terran 1 rocket once before deciding to concentrate on the Terran R. It's a big heavy-lift rocket - perhaps 50% bigger than Falcon 9. That means it's an expensive rocket to develop, and it's not clear to me whether Relativity has the money to make it to the finish line, nor the ability to effectively compete.

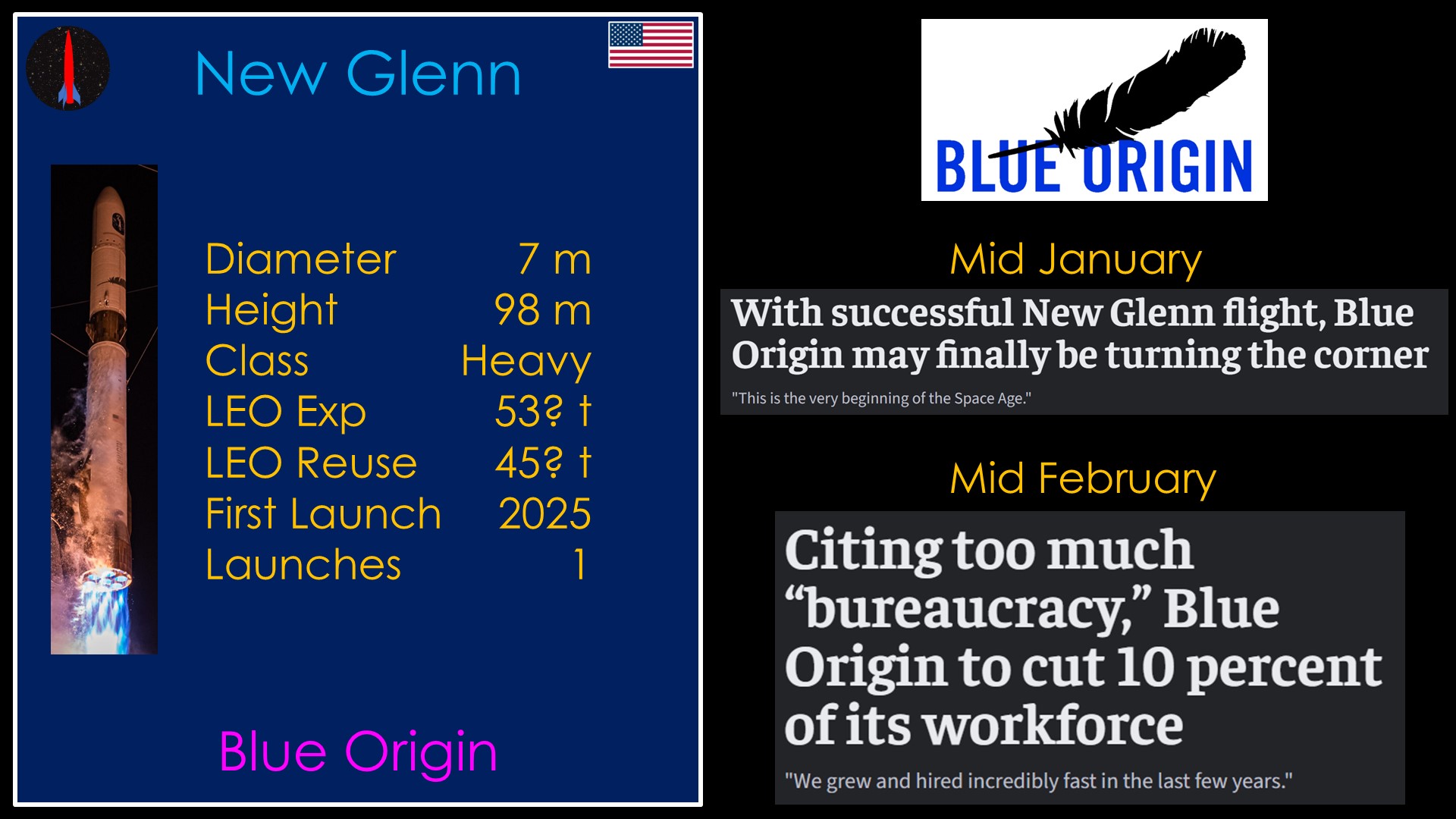

After years of delays, New Glenn finally took flight and successfully got into orbit. That was a big accomplishment.

And then, less than a month later, Blue Origin decided to cut 10% of its workforce.

It's not that I don't think the Blue Origin could use some reductions. From what I can tell, they've had years without significant fiscal controls and in that sort of environment you generally do end up with too many people, or people allocated differently than you want them.

It's that this decision makes so little sense from a business perspective.

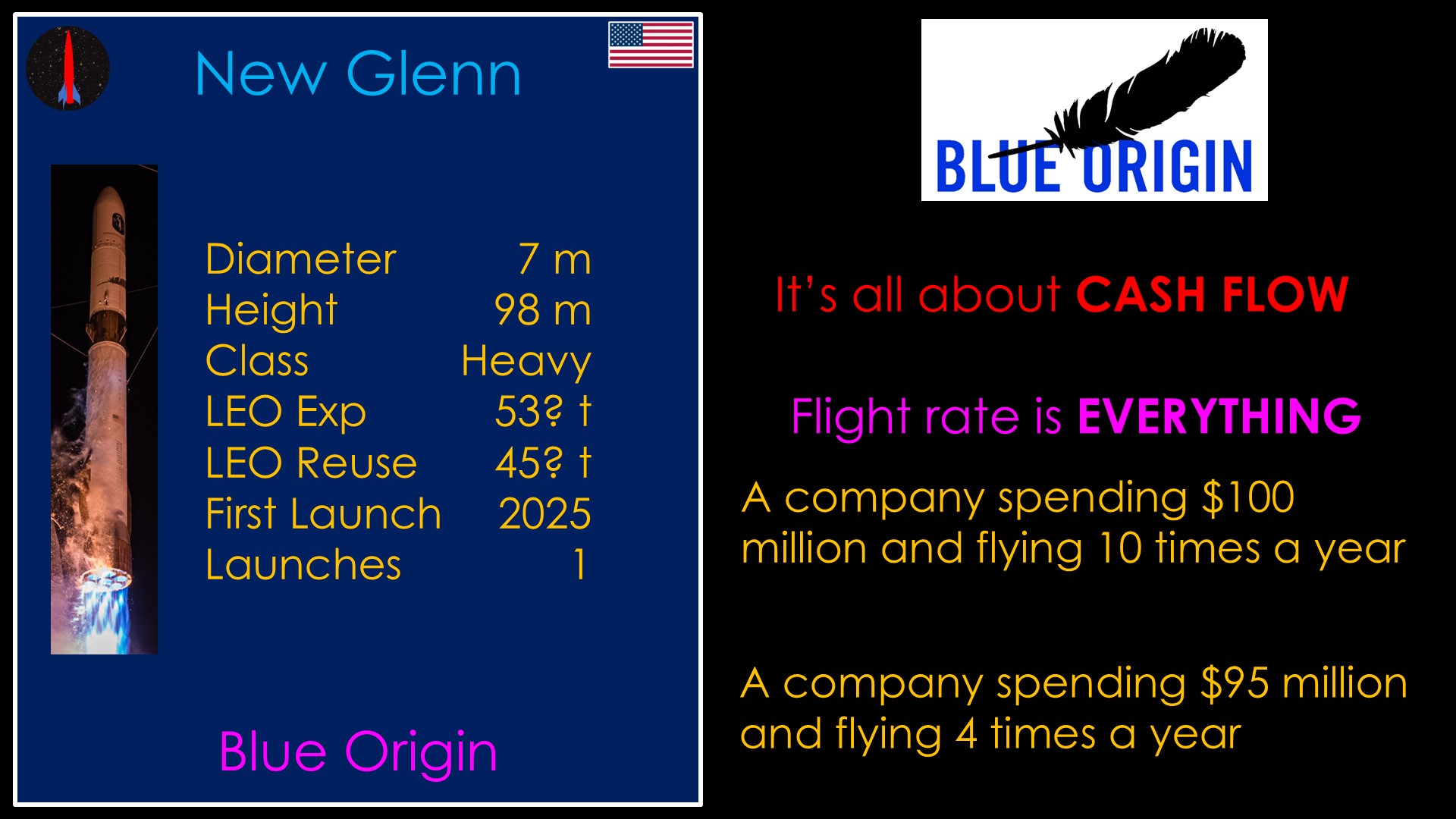

In business, it's all about cash flow. You have fixed expenses and you need to be bringing revenue in to cover those expenses. If you don't, you are cash flow negative and that's not something that can last in the long term.

In the launch business, you bring in revenue by flying customer payloads, and that means that flight rate is everything.

Which would you rather have?

A company spending $100 million on fixed costs and flying 10 times a year?

Or a company spending $95 million on fixed costs and flying 4 times a year?

Once you get your first rocket flown, you want to look carefully at all the things that might slow you down and carefully deploy additional resources to do what you can to address any bottlenecks you find. It's a little pricier in the short term but it's the only way to get to a flight rate that will allow you to compete.

That is why the layoffs made so little sense to me. Some of the layoffs probably create new bottle necks to higher flight rate. Some other people aren't happy about the layoffs and they are going to go elsewhere, and that is usually your best people who can easily find work elsewhere. And they took the huge morale boost that everybody in that company got after the launch of New Glenn, and replaced it with fear, uncertainty, and doubt.

I want to be able to root for blue origin but they make it so hard.

The only scenario where the layoffs make some sense is if you don't actually have customers ready to launch so ramping up your capability would not result in more launches. This is a possibility - I only see 4 new glenn launches in their public backlog, and two of those are internal launches for Blue Moon.

Management is making choices that will slow down their ramp up to a higher flight rate. Maybe it's bad choices, maybe they just don't have the customers they want. I don't think either case makes me particularly optimistic for the future of New Glenn...

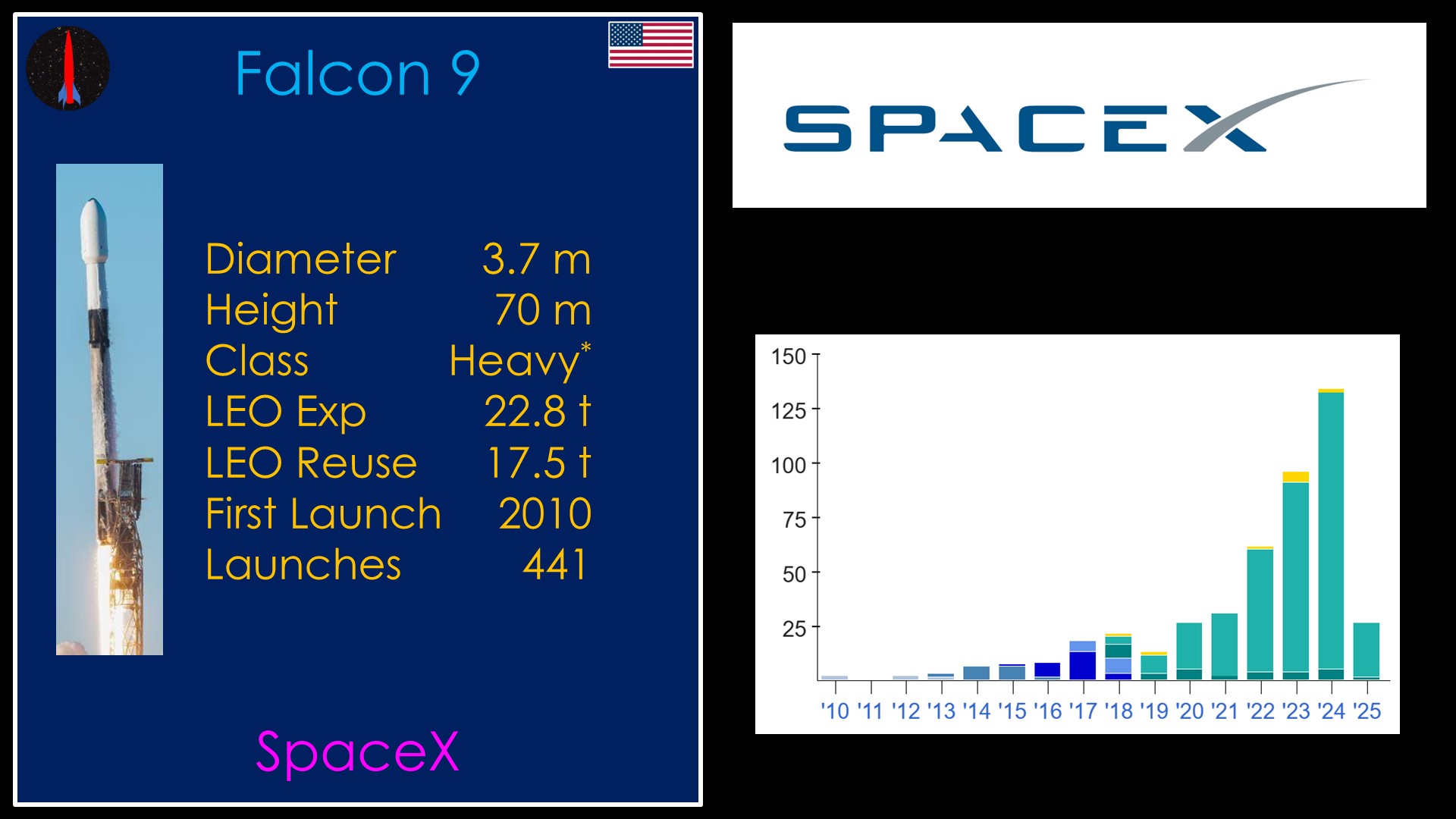

Which finally brings us to space exploration technologies. I always find it funny when people talking about SpaceX feel the need to use their whole name.

There's very little to say about Falcon 9 that hasn't been said - it's the most successful commercial rocket ever. I don't think many expected they would be launching as often as they have or be as dominant as they've become - the only markets that they don't dominate are those that are structured to prevent domination - the NSSL launches, the NASA ISS crew and resupply launches, and the "everybody except SpaceX" Kuiper launches.

They did 134 launches in 2024, despite some brief issues.

Falcon Heavy is a big brute of a rocket that is fun to watch, but it's probably a commercial failure. In 6 years it has flown only 10 customer missions.

It was still probably a good idea for SpaceX to build it as it enabled them to get a bunch of Falcon 9 NSSL launches, which have been very lucrative, but there's just not that much call for this sort of rocket.

Note the asterisks in the payload numbers. Because Falcon Heavy uses the same second stage and payload adapter as Falcon 9, the LEO numbers are only theoretical - they would require custom second stage and hardware that does not exist.

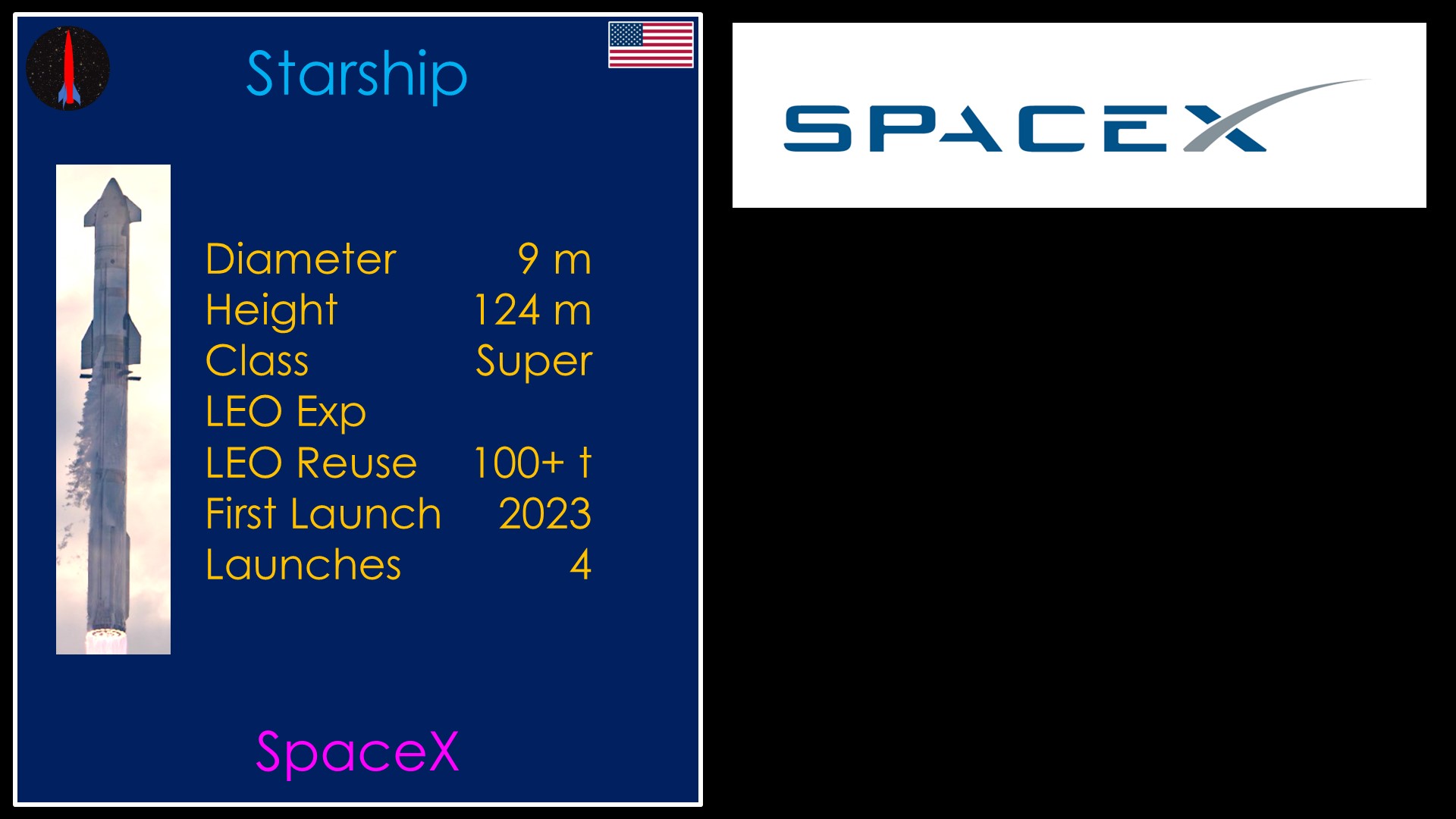

And that brings us to Starship, a launch system that during development has been both hugely impressive and annoyingly unreliable at the same time.

With 3 out of 3 successful tower catches, it seems likely that SpaceX will soon be flying boosters more than once and that will make the development program considerably cheaper and perhaps faster.

They are still in research mode for the ship and are making significant changes.

Starship is a weird rocket as it wasn't built to compete in the commercial launch market. It's intended to launch the much bigger starlink V2 and V3 satellites and it exists for SpaceX's Mars plans, but it is ridiculously oversized for the current launch market.

If it achieves cheap reuse then maybe it's cheap enough to fly the sort of payloads that fly on Falcon 9, and it's possible there might be a robust market for bigger payloads at some point. But it's still a question mark.

That's all the rockets. Now it's time to rank the companies. We'll start with tier 1 companies.

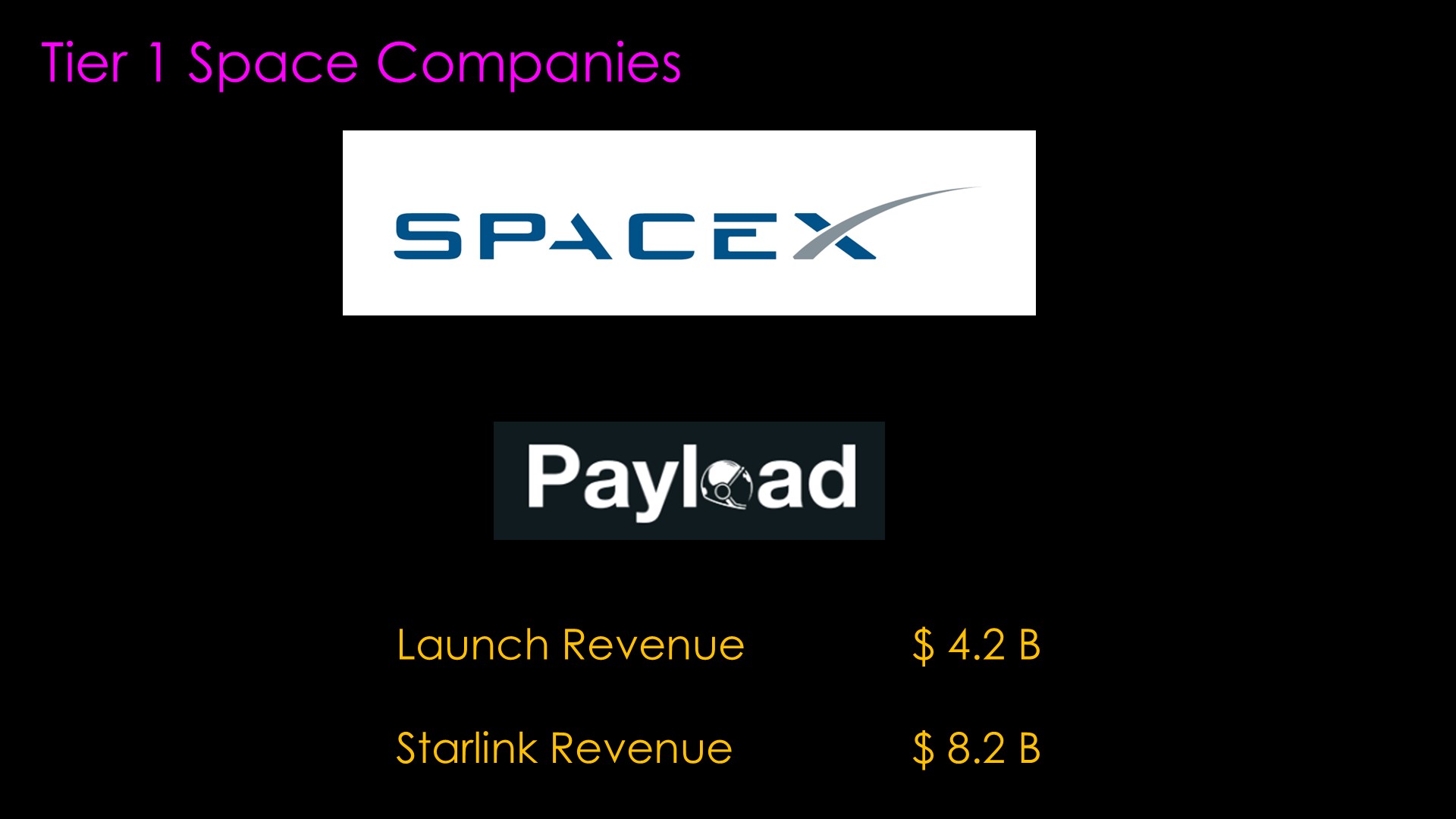

SpaceX is the only tier 1 company. But along the way to dominance, something unexpected happened.

The most successful commercial launch company ever is no longer a launch company.

Payload space build a model to estimate SpaceX revenue, and they recently released their numbers for 2024.

Their estimate is that SpaceX collected revenue of $4.2 billion on launch. That is a lot of money and is likely greater than the revenue of all other US providers combined.

But it's just a little more than half of the Starlink revenue and with the current Starlink growth rate, this number is only going to go up. SpaceX is now primarily a telecommunications company with a launch business on the side.

From a company success perspective, they need starship launching new Starlink satellites as soon as possible, and that's why we've only seen the starlink dispenser in the payload bay. More starlink is now what drives the company revenue.

That will change the dynamic in ways that I don't think are clear.

Further, SpaceX no longer has a founder who is highly focused on everything the company does; Elon Musk has many other interests. I'll be talking about that more in the future.

Looking at tier 2 - those that are mostly likely to compete with SpaceX - I only see two candidates.

Rocket Lab and Neutron is the most likely one. Neutron is Falcon 9 version 2.0, a rocket that SpaceX decided to skip because they wanted to do Starship. It's not a huge jump forward, but it's likely to work well and Rocket Lab knows how to ramp up launch rates. And SpaceX has been focused on Starlink and starship for a long time.

Rocket lab is the only other US launch company who is regularly launching rockets right now, and that experience gives them a leg up.

The second member of this tier is Stoke. I've been fairly skeptical of them in the past but they are making nice progress and I think they have bitten off an appropriately-sized amount of technological challenge. Nova is a harder system to make work than Neutron, but it could end up being cheaper and has the chance to be a good architecture for humans.

They both end up here because they have chosen markets that should play well against SpaceX and I like how the companies operate.

Tier 3 is meaningful market participation, which you can look at as "flies a lot".

ULA has a lot of experience, but Vulcan is an expendable rocket and in the long term it's not going to compete meaningfully with the partially or fully reusable architectures. It can probably play in the anything but SpaceX market if that pans out and perhaps in NSSL, but as I noted in the markets video, both of those markets are in flux.

The other candidate for this tier is blue origin.

I remain skeptical about their ability to take a company that has not operated commercially and convert it into one that can compete with companies that have commercial experience. Maybe they'll get there, but they only get a half membership here.

I couldn't come up with a polite name for these, so I'm calling them "other launch companies".

I expect they'll fly some but I don't expect that they will do anything surprising or noteworthy.

Avio has built a business out of Vega C launches in a market that is largely without any competition. That is going to change.

Either E sair aerospace or rocket factory Augsburg are going to get into orbit. They will offer cheaper launches than Vega C, and they also both have agreements to run rideshare companies. Europe has generally preferred to launch on their own vehicles even if the launch costs more, and I expect the Musk/Trump effect to push a lot of business their way.

I think Avio is going to have a hard time competing with these small nimble companies, which will be great for European space.

Outside of the US, JAXA doesn't look like they want to make a serious run at the new world of launchers, and it seems unlikely that Arianespace is going to be able to get agreement to move quickly.

I expect that ISRO is going to keep growing at a fast pace and I would not be surprised if they surprise us.

China is complicated. The US does not issue export licenses for US payloads to launch on Chinese rockets. There are other countries that do the same and some that do not, and that makes the market definition confusing.

I don't talk about Chinese rockets because I don't know enough about them, but I did ask my TwiX followers for suggestions to be better informed, and here are three of them.

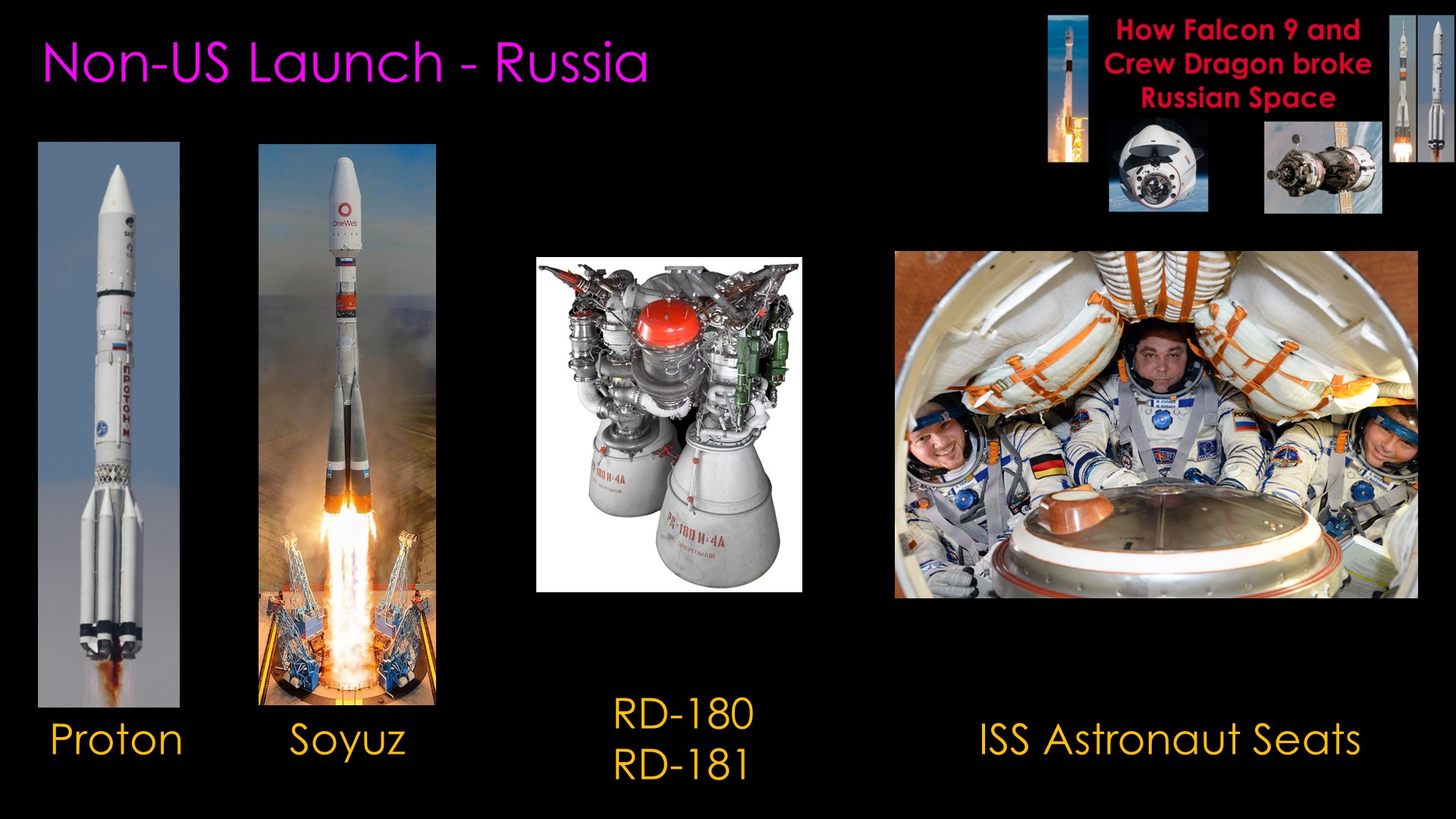

And what about Russia?

In the old days, Roscosmos launched commercial satellites on Proton from Baikonur. Roscosmos launched commercial satellites on Soyuz from both Baikonur and from French Guiana in cooperation with Arianespace. Russia sold engines for the Atlas V and Antares launchers. And Roscosmos sold rides to and from the international space station on Soyuz rockets.

That was a good business - it brought in quite a bit of revenue.

Proton launches went away because Falcon 9 was as cheap and more reliable. ISS astronaut seats went away when Crew Dragon came online.

The reliance on Russian engines became politically untenable when Russia invaded Crimea.

Russia decided not to work with Arianespace on Soyuz launches any more and impounded 36 OneWeb satellites that were going to launch on Soyuz from Baikonur.

Russia does not have a commercial space program any more, and since they stole 36 satellites from OneWeb, it's unlikely that anybody is going to trust them in the near future.

If you want more details, see my video "How Falcon 9 and Crew Dragon broke Russian Space".

And that's what I think about the current world of rockets and organizations.

With 5 rockets planned to take their first flight in 2025, it's going to be an interesting year.

If you liked this video...

I'm too tired of rockets right now. You make the joke.